An Engineer’s ABCs of Thoughts on Design

There are no hard and fast rules for achieving success in design, but there are principles of good practice. Here are some of my feelings on the subject, some thoughts and observations ranging from A to Z:

Aesthetics. How something looks is always important. This does not mean that it has to be a work of art, just that it should look appropriate to its function.

Bugs. It is always better to assume that a design contains a bug than to believe that it does not. A designer should never check a design without having a supply of insecticide handy.

Constraints. There should always be strings attached to a design idea; they keep it from floating off into irrelevance.

Design. This is the most creative and most fundamental aspect of engineering. Other engineering activities, including engineering science, should be in service to design.

Economics. The self-made American engineer Arthur M. Wellington (1847-1895), in his book on the economic theory of the location of railways, defined engineering as “the art of doing well with one dollar, which any bungler can do with two after a fashion.”

Failure. This thing that designers want most to avoid should always be first and foremost in their mind. Otherwise, how could they design against it?

Glass Part Full. It has been said that engineers view a partly filled glass neither as optimists nor as pessimists: They simply see the glass as improperly designed.

Harmony. The members of any good design team should fit together like fingers in a glove: They need not lose their individual identities to work well together.

Inventiveness. Engineers are as creative as inventors. Engineers just call their inventions designs.

Judgment. Not all aspects of engineering can be quantified. Among them is judgment. This comes with experience, and it enables an engineer to make the right choice when there are no easy numbers to serve as guides.

Know-How. Technical skill, also known as know-how, is a wonder to behold, whether in analysis or design.

Lessons Learned. The old saying, “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me,” applies to things made by people as well as to the people themselves.

Mind’s Eye. This term has been used frequently by engineers to refer to their nonverbal visualization of concepts and designs. James Nasmyth (1808-1890), the Scottish engineer who invented the steam hammer, wrote at the time of its conception, when he sketched it out in his notebook, of “having it all clearly before me in my mind’s eye.”

Neatness. Neatness always counts. A cluttered design, like a messy desk, can give an impression of disorganization. It may be a false accusation, but why risk it?

Over-design. What overeating does to a person, over-designing does to a product.

Prototype. Nothing can be more beautiful to a designer than an ugly prototype that works.

Quality. There is nothing more satisfying than a device that boasts quality of concept, quality of design, quality of components, quality of assembly, quality of appearance, and quality of operation.

Redesign. If designing from scratch is akin to art, is redesigning akin to art criticism?

Sketch. At the conceptual design stage, a sketch can be worth a thousand sentences.

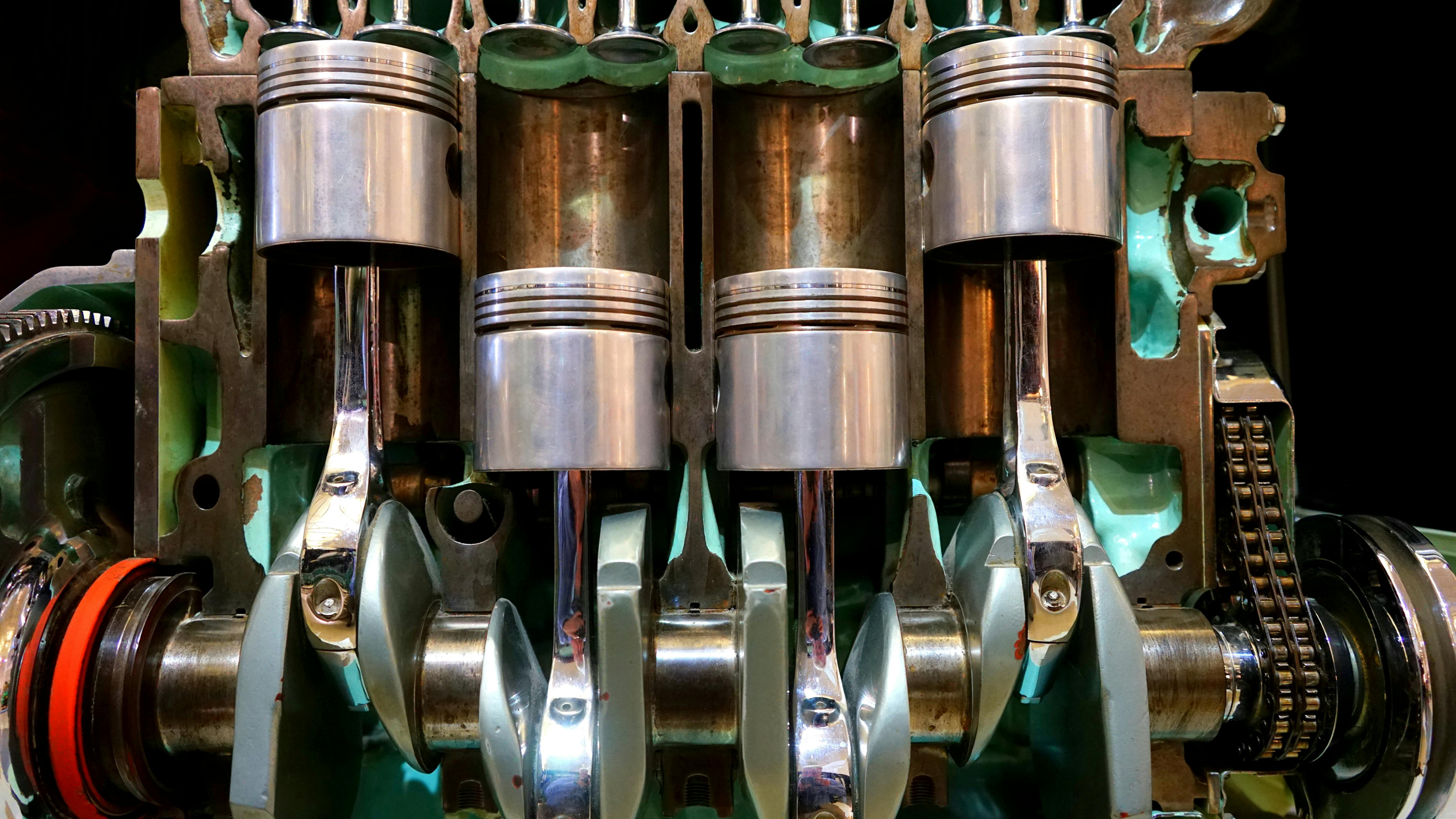

Theory. Throughout the history of technology, there has been the desire to make devices, like the steam engine and airplane, for which there was insufficient theory on which to base design decisions. Sometimes engineering accomplishment has to precede scientific understanding.

Unknown Unknowns. Designing something that goes beyond the envelope of experience necessarily involves venturing out into unknown territory, where the “unk-unks” hide.

Vision. Design without vision is like eyeglass frames without lenses.

Worry. According the British aeronautical engineer James E. Gordon (1913-1998), writing of innovative designs, “It is confidence that causes accidents and worry which prevents them.”

X. Embarking on a radical new design is like striking out into the unknown. While the letter x is associated with the unknown, it also marks the spot.

Yes. Confronted with a design challenge, it is scientists — who think they know Nature’s secrets — who are likely to say, “No, it can’t be done.” Engineers are more likely to say, “Yes, we can do it.”

Zen. In 1974, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, by the American writer Robert Persig, was published; it has been assigned reading in many an engineering design course since. The book is a meditation on the nature of design and the idea of quality, good things for any designer to reflect upon.

latest video

news via inbox

Nulla turp dis cursus. Integer liberos euismod pretium faucibua